THE ROUTE

Sydney to Brisbane January 5 through 14 2009

Brisbane to Thargomindah: January 15 to January 26 2009

Thargomindah to eyre Peninsula

January 27th through February 7th 2009

Port Lincoln (South Australia) to Geraldton (Western Australia)

February 8th through March 7th 2009

Geraldton to Broome (Western Australia)

March 10th to April 10th 2009

Cape Leveque and Gibb River Road

April 14th through April 28th 2009

Gibb River Road to Alice Springs

April 29th to May 15th 2009

Trip Mileage since Sydney: 19300 km

We have arrived now in the center of the Australian continent and are sending greetings to you from Alice Springs.

We departed Home Valley Station in the Kimberleys at the end of April with course set for the Bungle-Bungle or Purnululu National Park. The last 100km on the Gibb River Raod involved the widest river crossing yet, the 200m wide Pentecost River. Martin managed to steer the car safely to the other side, even though the water level was at points rather deep and our car does not have a snorkel.

After the river crossing, the road wound its way along the foothills of the Cockburn Range

toward the small township of Kununurra. From here we headed south to Purnululu National Park, or the Bungle-Bungles.

Secluded by distance and the surrounding mountain ranges, the Bungle-Bungles remained hidden from the prying eyes of tourists until 1982. Previously, they were known only to local Aboriginals, helicopter pilots and a handful of cattle drovers. After being featured in 1982 in a TV documentary on the scenic wonders of Western Australia, the area became an instant hit and was finally gazetted as National Park in 1987.

The Bungle Bungles are made up of towering rocky domes

which soar up to 250m above the surrounding plains and stretch to the horizon in an intricate maze of red-lined rocks. Deep gorges cut through the terrain. Wind, water and forces of erosion have moulded the domes into beehive-like shapes.

We explored them initially on foot, taking walks through the winding gorges; and later also in a chartered helicopter. The doorless, open-air feel of the helicopter proved a bit of a challenge to Martin, who is not very comfortable in great heights.

However, the stunning vistas and the incredible landscape below us quickly helped to recover shaky nerves.

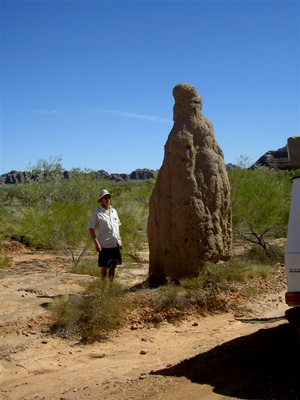

Back on the ground we came across termite structures trying to emulate the shape and dimensions of the beehive-domes of the Bungle Bungles. Some termite buildings had already achieved impressive heights,

while others bravely set forth construction in the middle of the road.

Our last stop before heading on the Canning Stock Route was Halls Creek, a sad and somewhat run-down sort-of-a-place. Like many other townships in the northwest, Halls Creek suffers from alcohol related problems among the town's resident Aborginal population (violence, domestic abuse, family disintegration). Strict legislation has been passed to curb alcohol consumption and to prohibit drinking in public places, but during the night one heard many a drunken brawl passing by on the streets outside the Halls Creek campground. Although Halls Creek is a major traffic node along the northern east-west axis, its shops offer virtually no supplies for the travellers: the shelves were mostly empty, and the only things that seemed to flow in abundance were beer and grog. We were glad to be leaving the town after a one-night stop-over. From Halls Creek we drove straight to Bililuna, the northern entrance point onto the Canning Stock Route and the Great Sandy Desert.

The Canning Stock Route (CSR) stretches for over 1700KM across the arid heart of Western Australia. It is the longest and hardest 4WD track in Australia, and probably one of the last great adventures left on earth. It passes through vast uninhabited country-side, and has few permanent or temporary waterholes. The last one we found was right at the start of the track, south of Bililuna at Stretch Lagoon, were we made first camp.

Due to run-offs from rains up north, the lake carried ample water and had attracted many birds.

The CSR was orginally built by Canning and his team of workmen, traversing the barren countryside on foot and with pack camels. Beginning in April 1906, they built over a period of 2 years a sequence of 54 wells for watering mobs of cattle, which were pushed by drovers from the Kimberleys to the southern goldfields near Kalgoorlie. One of the great attractions of travelling the CSR is the sense of history that pervades most of the wells dotting the track. The CSR today follows fairly closely the original track by Canning and his team.

Cutting initially through spinifex grasslands,

the CSR then heads right into desert country. The tracks are no longer maintained and the burnt out car wrecks tell their own story of broken down dreams.

The challenge in driving the CSR consist of finding the RIGHT track to follow (frequnetly there are many tracks left in the sand leading to nowhere in particular), road signs are tiny or hard to find.

Once you have identified the right track, you then need to get the car safely across hundred and hundreds of sand ridges or dunes. Travelling the CSR from north to south, we encoutered early on the sandhills of the Great Sandy Desert. The sandhills must be crossed head-on. Camp is made usually near one of the wells,

many are defunct and dry, but others have been reconstructed to their original condition, or modernized for drawing water by bucket.

In the Great Sandy Desert, the red sand ridges dominate the landscape.

Unlike sand dunes in the Sahara, the sandhills in the australian desert can be many kilometers long, varying in height between 8-30 meters, and are covered on the slopes with spinifex and other hardy vegetation. The track upward runs through deep and soft sand, and even with reduced tire pressure we got bogged several times. The only remedy then is to dig the car free, back down the hill and with some luck find enough flat and hard ground to get the car up to speed and over the sandridge.

In order to help us find the right track along the way, we decided on a division of labor early on: Martin doing the driving and car maintenance, and Gabi setting the course along the way. This meant that at each well, new coordinates had to be set up for the GPS system to guide us.

But even with the help of technology we sometimes had to backtrack and figure out exactly where we were. We got badly lost once, close to the finish of our portion of the CSR, and drove around in circles and zig-zag patterns for an hour before identifying the correct track to follow.

The initial opening up of the arid heartland of Western Australia could not have been accomplished without the use of camels (or, correctly, dromedares). They were imported in great numbers along with camel drivers from the Middle East. After the development of roads and railways, the camels became superfluous and were set free to roam the desert country. Today there are over 1 Million wild camels wandering through the deserts of Austalia, and we saw many of them on our journey along the CSR.

Because the area is so remote and pristine there is quite a bit of wildlife to be seen. Wild dingoes are numerous

and we often heard their haunting cries at night in our roof-top tent.

Between the sandhills the landscape is dotted with numerous barren clay pans and salt pans, like here at Well 45.

In the valleys between the sandhills dense spinifex grow, not only on the side of the track but also right in the middle. Their hardy needle-like stems break easily and they clog up the radiator within short periods of time. One task after pulling into camp in the evening was to clear the radiator with air pressure from the debris of spinifex collected during the day. Servicing the car before night fell became part of the evening routine

(fueling up from jerry cans, pumping up tire pressure, cleaning out radiator). Generally this meant getting the car ready for the challenges of following day.

Some of the most beautiful campsites along the CSR we found in dense stands of desert oak trees.

The desert oak is a slow growing wood which also makes good firewood for a warming campfire during the chilly desert evenings.

Daytime temperatures rise well into the 30° Celsius, but temperature fall into single digits (around 4°C) at night. During one night it hovered around freezing. We slept with 4 sleeping bags, long trousers, socks, sweatshirts and fleece jackets and were still shivering in the roof-top tent. One morning Gabi found a thin layer of ice on the car. But you would not have guessed the chilly nights while driving under blazing blue skies during the day and sweating under a hot sun while digging the car out of another sandhill, or stopping to watch the wild camel carefully treading their way through thorny spinifex country.

Unlike most outback tracks we have travelled in Australia, the CSR no longer cuts through cattle country, and the last mob of cattle was run south in 1958. One thing left behind are all the bush flies and they proofed to be the same nerve-wrecking nuisance as elsewhere in the country-side. Getting up before the flies wake up, meant to be able to enjoy one's coffee around sunrise at 6AM, and then have camp packed up and ready to go when the sun thaws the swarms of flies around 7:30AM.

At Well 33 in Kunawaritji Aboriginal community we left the CSR, fueled up and took at long last a cold, open-air shower from the hose attached to the water tank.

We headed due East to Windy Corner for a night's campsite,

and then along tracks so lonely that people had just left their car right in the middle of the track after it broke down some months or years ago.

The track was often shared with camels,

whose tracks we followed for miles on end before catching up with groups of them.

From now on, we travelled for hundreds of miles along the 'outback highways' cut through the countryside during the early 1960s by australian legend Len Beadell, who surveyed, constructed and named many these outback tracks with his Gunbarrel Road Construction Party. At major 'traffic junctions', like here Gary Junction, guest books are set up in his honour.

Many of his original road signs are still in place.

The tracks offer beautiful spots for lunch along the roadside,

or to chase camels off the tracks --like here near Mount Leisler.

Even the crossing of the border from Western Australia into the Northern Territory is marked by an original sign from Len Beadell from the 1960s.

Travelling through the northern part of the Gibson Desert on Beadell's outback tracks, the road passes through land which has been given back to Aboriginal populations, such as the Pintubi at Kiwirrkurra and the Ngaanyatarra further down on Sandy Blight Junction Road. Most of the Aboriginals who returned to their native lands live along desolated looking station, called Communties, made up of corrugated housing, school, clinic, and a general store and fuel tank managed by resident white people. Along the road the most frequent sight of a car was a wrecked car, many of them dot the countryside on Sandy Blight track.

A couple of water bores are left in place for travellers to pump salty bore water from underground artesian wells.

Sandy Blight Junction Road leads eventually onto the Great Central HWY,

along Aboriginal communties who struggle with alcohol related problems and have tried to find their own way of handling it.

Long after the last camels were sighted, we actually came across a camel traffic sign, a reminder to us that we were approaching civilization again.

Cruising along Great Central HWY we entered the Kata Tjuta and Uluru National Park through the back door, and took our obligatory pictures of these tourist attractions

Kata Tjuta/the Olgas, and

Uluru/Ayers Rock. After weeks of cold nights in the desert, we pulled into Curtin Spring Roadhouse (and working cattle station) and rented a heated cabin for one night with hot showers and a cooked breakfast next morning under the stations orginal bough shed.

This is were the farm family had lived for three years after their arrival on the station in 1956, with a spinifex roof over their head and not much else to speak of. From there we drove on to Kings Canyon in the MacDonnell Ranges,

and spent our wedding day anniversary on a rescue mission that lasted 2 days. Heading out of Kings Canyon on Mereenie Loop Road we came across a broken down car belonging to a young couple from Israel. They were totally inexperienced travelling on gravel roads, knew virtually nothing about the inner workings of their australian Jackaroo Holden, carried almost no spare drinking water and were faced with a major leak in their radiator. When we found them we were all about 140KM from the nearest communitiy at Hermannsburg along a badly corrugated gravel road. Martin quickly determined that the car was undrivable in the current condition and that the radiator had to be replaced.

We decided to tow them all the way to Hermannsburg with Gabi driving our 300GD and towing the Jackaroo with Martin at the steering wheel. We crawled at a speed of 30-40km/hour and had to make camp along the track before we reached Hermannsburg and handed the car and the couple to a friendly mechanic at the fuel station. Two days later we met the young couple again in Alice Springs with a new radiator installed in their car and on their way to Darwin.

For us as well our journey draws to a close and we have begun preparations for our return and the return of the car to Germany. After having driven over 19,000km through Australia , we will tackle the last 3000km back to Brisbane in a leisurely manner. The car is still in one piece but the desert tracks have taken its toll: at least one of the tires is loosing air, the wheel bearings on the front axle are worn out, the main break cylinder is playing up at times and there are other minor troubles which Martin has found worriesome about the car.

So, hold the fingers crossed that we will be making it in one piece to the container in Brisbane to send the car back to Germany for some serious repair work to be done. From the heart of the continent we send you all many greetings.

Next Route:

Alice Springs to Brisbane

May 17th through June 17th 2009

February 8th through March 7th 2009

March 10th to April 10th 2009

April 14th through April 28th 2009

April 29th to May 15th 2009

May 17th through June 17th 2009